Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia, and is predicted to affect 1 in 85 people by the year 2050. And unlike stroke, prostate cancer, heart disease, and HIV, diseases in which we have made progress in treating, Alzheimer's disease has been increasing in prevalence as a cause of death. While this is probably partly due to the fact that we have been living longer and Alzheimer's is typically (but not always) a disease of the elderly, there is no denying that Alzheimer's is a disease in need of attention.

There are a few existing Alzheimer's treatments that can provide mild relief of symptoms, but none halt or even slow disease progression. Why have we not been able to come up with an effective treatment for this increasingly common disease? Here's one reason - we're not even sure what causes the disease!

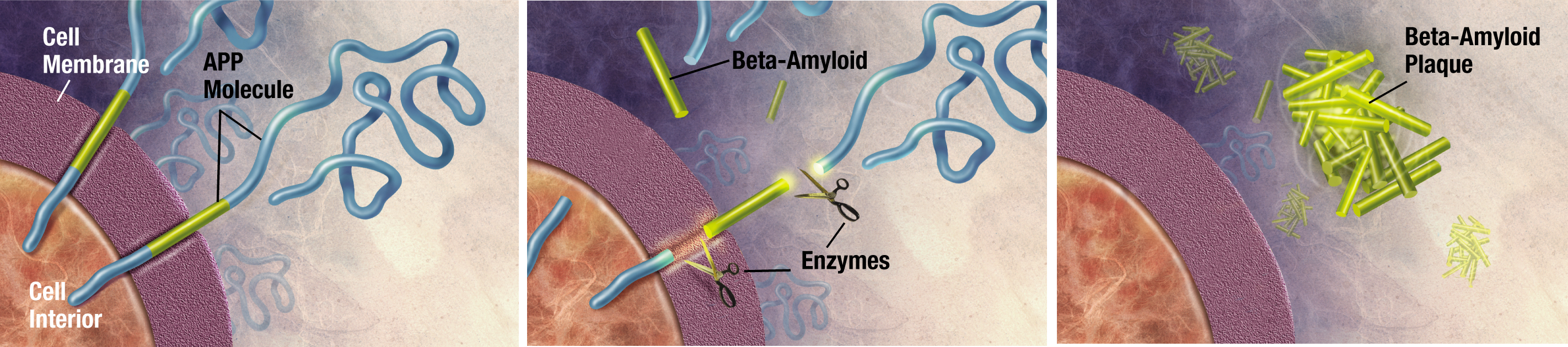

A prime suspect in the disease are amyloid-beta proteins. These proteins may have accomplices that also cause Alzheimer's, but amyloid-beta proteins play a definite, if not starring role. Amyloid-beta proteins are misfolded chunks of another protein, creatively named APP for amyloid precursor protein. I use the word "chunks" because the bits of the protein that misfold and form aggregates are made up of pieces of a larger protein that gets cut up by enzymes, as shown below.

Image credit: ADEAR: Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center, a service of the National Institute on Aging

What does the full-lenth amyloid precursor do as it's chilling outside the cell, all floppy and blue? (Note: proteins are not actually blue and cartoony as shown in the above figure. They are very tiny.) We don't even know that! We do know that when amyloid-beta begins to misfold, it aggregates with other proteins and that these aggregates probably cause neuron damage. Other neurodegenerative diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or Parkinson's are also linked to these aggregates of misfolded proteins, generally called amyloids.

Get out your tarp, because this might blow your mind: what we call protein "misfolding" in Alzheimer's and other diseases may actually be related to the normal activity of these proteins! What else besides protein misfolding and neurodegneration ties together Alzheimer's, CJD, and Parkinson's? We don't know what any of the precursor proteins in those diseases as their normal functions. It COULD (big emphasis on the could) be possible that some of these proteins are meant to be sometimes be folded in the amyloid state, and that these neurodegenerative diseases are caused by an upset in the natural equilibrium of "normally folded" and "misfolded" amyloid states. I plan to blog more on protein folding and amyloids but here's a teaser for another paper I will cover - amyloid proteins may help explain how memory works.

Now that I have not-definitively-at-all covered the background of Alzheimer's, let's get to the paper I want to talk about today. This paper, "ApoE-Directed Therapeutics Rapidly Clear Β-Amyloid and Reverse Deficits in AD Mouse Models," [@cramer_apoe-directed_2012] was published in March as a ScienceExpress article. This means that the editors of the journal Science thought it was important enough to rush out and publish online. Added bonus for overworked grad students like myself - ScienceExpress papers are short!

Punchline

The authors of this paper do something kind of amazing - they find a drug, bexarotene, that they can give to mice with Alzheimer's and almost immediately clear out the deposits of aggregated amyloid-beta protein that build up in the brains of people and mice with Alzheimer's. Even better - this drug is already FDA approved for the treatment of cancer. And as chemotherapy drugs go, its side-effects aren't that bad, so we know we can give it to humans relatively safely.

How amazing is this drug? The authors take images of brain slices from mice pre and post treatment. Aggregates of amyloid-beta can be visualized and counted by adding a florescent antibody. After only three days, the amount of aggregated protein in both the cortex and hippocampus of affected mice has decreased by nearly half, and the decrease continues for several weeks. This is great!

The authors also show that not only do the plaques that may cause the disease dissipate, the mice also experience restored memory and cognition, which would be an amazing result if it holds in humans. In mice, building nests is a social behavior that healthy mice can perform but that Alzheimer's-affected mice cannot. After treatment with bexarotene, nest-making ability in diseased mice was restored. Bexarotene treatment also restores the sense of smell in Alzheimer's mice, another great sign because humans with Alzheimer's also experience loss of smell.

How does the drug work? There is a protein called apoE naturally expressed in your neurons. This protein gets secreted out, attaches itself to amyloid-beta aggregates, and helps break down these aggregates. apoE encourages microglia, helper cells in your brain, to eat up through phagocytosis amyloid-beta aggregates and then to break down the aggregates. Everyone's brain, even in people with Alzheimer's, already makes apoE and breaks down amyloid-beta aggregates. Alzheimer's could be caused by an inability to break down amyloid-beta fast enough (like healthy people do), so making more apoE could reverse the disease.

So we have a cure for Alzheimer's right?

Right! ... for mice. Anyone who's ever read about an amazing cure for a disease found in mice already knows that this cure is not likely to work in humans. Although mice have versions of 99% of the proteins we have, we also share a majority of our genome with plants. And as much as I try, laying in the sun does not make me full, just sleepy and full of vitamin D, so simply sharing similar genes does not make me the same as a mouse or plant. It's particularly tricky to translate a therapy for a neurodegenerative disease from mice to humans, since we think so differently than they do, at least based on my conversations with mice.

A further complication are the mice we perform Alzheimer's research on. In order to do this research, scientists had to create mice that could serve as models for the human disease. This was done by inserting in human genes that cause Alzheimer's, creating an imperfect model. Mice models of disease do not show all of the symptoms that humans with Alzheimer's do and may in fact be better models for early stages of disease progression than late. If so, bexarotene may be able to be used as a preventative therapy, but not as a cure.

Even with these grains of salt in mind, I still found this paper very exciting. I look forward to seeing what the results of ongoing clinical trials of bexarotene as an Alzheimer's therapy in humans will be. With a little luck, this drug can succeed where so many other promising drugs in mice have failed and become a useful therapy in humans. If a loved one of mine had Alzheimer's, I would be watching the clinical trial results very closely.

Update (2016-09-16):

Multiple groups ([@fitz_comment_2013], [@price_comment_2013], [@tesseur_comment_2013], [@veeraraghavalu_comment_2013]) have since tried to replicated the results of this study, with only mixed success, at best (see Nature News for a good summary). Since the results of the study can't even be replicated consistently in mice, I have further doubts about the chances of bexarotene working in humans.